How is it possible to go on living – not just surviving but thriving – after an unimaginable loss? We have been asked this question so many times – generally by people who have not been bereaved.

This is strange because we cannot escape loss – no-one can – its part of the human condition.

The death of our son Joshua was not meant to be, but in the years following his death, we have found that our grief for him has been one of life’s greatest teachers. We have learnt not only that we can endure what we once believed to be impossible but that we still have choices. Grief has introduced us to a deeper appreciation of who we are and who we can become – that change is inevitable, and that we need to find strategies that will help us grow through the pain, to develop a more intentional approach to our grief and in the end be transformed in a meaningful way. Importantly and necessarily these are strategies that will prevent us from either being defined or limited by our loss.

The question we would now pose is – are the arts our means to this ‘transformation’? How can we use our individual and collective creativity to navigate through and grow from the trauma of Josh’s death?

In our view grief is almost by definition a creative process. It’s about filling the void left by our loved ones absence and it’s about finding ways to keep that love alive even after their death. If our grief is loaded with ‘what ifs’ and ‘if onlys’ then it’s also nourished by all those small (and perhaps daily) rituals we will inevitably perform as we remember them and honour them…. all creative acts.

This is our survival strategy – a way of reestablishing our own sense of identity, now shattered by the trauma of their loss, shattered because when they died part of us died too. But while Josh’s death awoke in us visions of our own mortality, we never lost being a mother and a father to him. He is still very much part of who we are. Our lives are formed by and still contain the essence of Josh. He is still our son. But to accommodate this idea, to accept his death as real while at the same time continuing to be his parents takes imagination as well as purpose. It’s a proactive approach to grief that we have found both creative and rewarding. By doing and making new things, photos, films, writings, this charity, all things that would not have existed had Josh not died, we have begun to find a way out of our nightmare and to make his death more real.

Here then are some examples of the transformative power of grief – things that we have done and things that others have accomplished.

RELEASED – a photo book by Jimmy

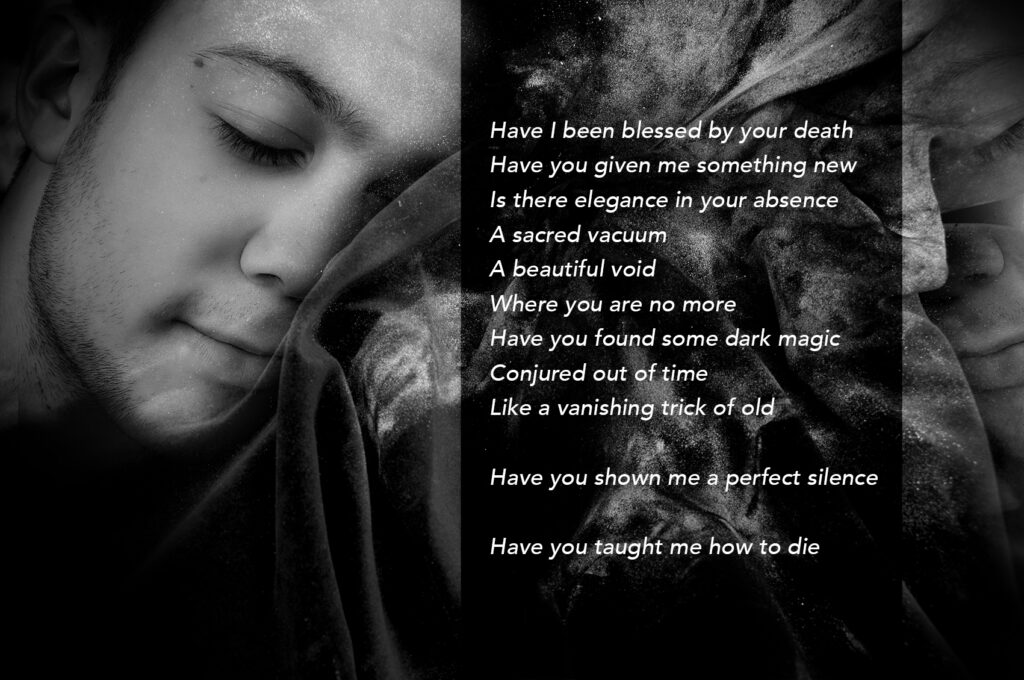

As we recorded in our last post, we have a new book coming out. When Words are not Enough is concerned with the way various people have employed their own creativity to express their grief. But what of an earlier work? If grief is a creative journey my own started with RELEASED – my first attempt at authorship – a book of photographs and writings that we (self) published just six months after Josh died.

So little time had passed before I started working on this project. Much of it was done in a complete haze so it’s difficult to say whether it was the transformative power of grief that produced the work or my own creative process that transformed my grief. But what did emerge was almost symbiotic relationship between my grief and my photography. Without going too much into the nature of photography and the theories around it (very art school!) what I discovered was a certain confusion, a “chaos of meaning’ lying at the heart of the medium that mirrored almost exactly my own bewilderment about Josh being dead. This became one of the key tenets of the book. We are all aware of the idea that photographs are a direct representation of reality (the camera doesn’t lie), yet they can never tell the whole truth. Every photo we have of Josh evokes a stubborn fantasy that he still has life (we all talk about the need to keep his memory alive), its a comforting illusion – up until the point we recognise that it’s just a photograph. A photograph of someone who is now dead. And that’s the point – most photographs will in some way outlive the person depicted – they are a fabulous resource to help us remember, at the same time a poignant, and very often painful, reminder of the reality of their death. Making Josh’s death more real has to be central to our future well being. Paradoxically then its the contradictions in his photograph that has helped me come to terms with that fact. But it’s only been by ‘reworking’ his image, trying out various montage techniques and by adding him to pictures that I make now (giving its historicity more presence if you like), that I’ve been able to secure my own sanity in this ‘madness’ called grief.

The title RELEASED was taken from the label on the plastic jar that contained Joshua’s ashes. It describes the status of his mortal remains, having been cremated, now being ‘released’ into the care of the funeral director and then to us. The book is available as hard and soft back (and as a digital download) from Blurb. Buy it or just take a peek and let us know what you think.

Our Active Grief Weekend retreats – transforming our creativity

Making and doing things a new, things that wouldn’t exist if our son was still alive.

Filling the void left by their absence.

This is the creativity that is at the core of our grief. A concept that we share with other bereaved parents and siblings who join us on our Active Grief Weekend retreats. But this is not ‘creativity’ in the professional or industrial sense, something we stress from the outset. Many will object – “but I’m not creative” to which we could reply – “are you curious?”

We’ve all wondered (in fact we cannot help but wonder) what our children would be doing now had they not died. As we recall precious memories our imaginings are also filled with ‘what might have been’s. So we tell the story of our grief. We need to tell it and to share it with others. It’s a way of validating our feelings, of helping us to truly accept the reality of our loss, and of maintaining that ever present and continuing relationship we have with our child. This can be hard especially in a culture that often has difficulty talking about such things so we chose our audience with care, but in the telling and in the sharing we are already being ‘creative’, we are choosing what to put in, what details to leave out. We are putting our own ‘spin’ on how we represent the events that have had such a huge impact on our lives.

It’s such a small step from the ‘telling’ to making something slightly more tangible, more concrete, more enduring, a new photograph, a new piece of writing, of turning your ideas into a more substantial creative act. Along with sessions on physical activity, we offer creative writing and photography workshops on our weekends and our ‘guests’ find that they really don’t need any previous ‘artistic’ experience or skills in order to create what are in effect new memories and new stories that will help them process their grief. One bereaved mother spoke of how her ‘creativity had been nourished’ throughout the weekend, another of how she had become ‘unstuck’ in her grief, yet another of her journey from private pain to public expression and of conquering the fear and the pain that came from looking at photos of their dead child. All testimonies to the transformative power of the creative expression of grief.

… and if we share our grief in this way, creating something new and beautiful from what feels horribly inimitable and peerless, but which is in reality a common experience, we have shared a very important insight about the human condition

Bereaved mother about her experience on an Active Grief Weekend

WILD SWIMMING – Jimmy ponders the transformative power of the open water

On the first weekend of September I’ll be swimming 10 kms down the River Dart – for charity, our charity. We need the funds to help those on low incomes attend our Active Grief Weekends. The annual DART 10K is the first and arguably the finest open water swimming event in the UK – comparable with the London marathon and its quite a challenge.

I have always enjoyed a good swim but since Joshua died I have found that swimming, especially wild, open and yes cold water swimming has had a truly transformative impact on my grief. Along with many others who will attest to the benefits of wild swimming to their mental health, I find that when I’m in the water and I get into the rhythm of my swim, stroke for stroke, breath after breath, I can achieve a kind of serenity – especially when I swim alone -there’s a peace here in this watery world that is so meditative, so in the moment and so far away from reality or the timescale of everyday living. Our friend, fellow wild swimmer and contributor to our forthcoming book, When Words are not Enough, describes how in the water she is ‘paused in a liminal space’ that mirrors the strange world in which she finds herself after her son Felix’s death.

I don’t suppose I’ll find that liminal space when I join 1600 others for the Dart 10K. But there are challenges … and there are challenges. Grief is a challenge. Some might say a lonely grief, one that you keep to yourself, one you leave unexpressed, is more of a challenge than a shared grief. Maybe diving into the cold waters of the River Dart with so many others, with all its comraderie, its physicality and the length of time I’m in the water (my aim is to complete in under three hours), will lessen the load or at least find some equivalence with the fact that while my grief is special to me, I am not alone.

In any case I do like a challenge … especially if it’s also for a good cause. And you can help me and our charity by giving what you can – click on the image below to donate.

Thank you and remember every penny goes directly to helping those on low incomes attend one of our Active Grief Weekend retreats where they will find new and creative ways of expressing their grief.

BEYOND THE MASK (60 mins) – Now free to view online

Every now and again events out of our control transform our grief from an intensely private experience to more social if not global phenomenon. Such was the covid pandemic during which so many people suffered losses in common with others that grief became a more or less collective encounter. More than that perhaps, covid provoked many of us to rethink our relationship to death, dying and bereavement and it turns out that many of our fears and anxieties around illness and mortality are mirrored in the way we respond to social difference and inequalities. While Beyond The Mask explores many of the aspects that both grief and the pandemic and lockdown share – isolation, the sense of time stopping, a loss of confidence, the challenge to ones sense of self, the impact on our mental health, and of course mask wearing and the various ways we need to adjust to a ‘new normal – the film also offers an insight into a crucial moment in our history. Of the many deaths of black and brown people in police custody, it was the murder of George Floyd at a time when all our freedoms were being called into question that the covid pandemic challenged many of us in the white community to recognise the pre existing violence of racism and the position of privilege that is afforded to white skinned people.

The virus of course affects everyone and the way we responded to it was a measure of our concern for everybody’s safety – to wear or not to wear mask in public, to get or not to get vaccinated – as much as anything these are signs of how seriously we take our responsibility to society as a whole, whether thats to do with looking after our health or addressing racist divisions.

Beyond The Mask is now available free of charge. Click on the button below. It’s free but we’d really appreciate a small donation to help us continue our work. Thanks.

A review of Memory Box, Echoes of 9/11 – a documentary film by Bjørn Johnson and David Belton

Last month Jane was invited by The Psychologist Magazine to comment on a new film about survivors grief following the 9/11 terrorist attack in New York. You can read the full article here.

Most documentaries will be made with the talents of an interlocutor, normally the director, who ask, encourage or cajole its contributors to tell their story. In Memory Box there is no interviewer as such. The film is made from footage that has been recorded with straight to camera testimonies from survivors of the 9/11 terrorist attack in New York. In the aftermath of the attack artist Ruth Sergel constructed a simple plywood video booth in New York City in which hundreds of people – survivors, witnesses, emergency responders, bereaved family, and friends of the lost – all entered to share their feelings about the trauma they had suffered. Twenty years later filmmakers Bjørn Johnson and David Belton invited many of these to re enter a similar video box and to reflect how their grief had changed. In both cases people were able to explore their experience of the tragedy without intervention from the directors or camera teams. Not only does the resulting film (an interweave of the by now well known news footage and selected moments from both recordings) paint an intimate portrait of human resilience, a poignant meditation on traumatic loss, it presents an intriguing portrait on the transformative power of grief.

The beauty of this film is that it provides a therapeutic container that is safe. You’re not trying to make it okay for other people when you’re in that box …. people can say it how it is without having to look into the eyes of someone else and think, oh, are they scared? Are they going to run away from me? Are they going to faint?

Jane in conversation with Counselling Psychologist Elaine Kasket for The Psychology Magazine

Those affected by a traumatic bereavement often suffer PTSD – post traumatic stress disorder – those who witnessed the attack in New York would naturally feel overwhelmed by memories, images, flashbacks and other sensory stimuli. Recalling his first impressions from watching the videos from Ruth’s original collection the director Bjørn Johnson recognised the incredible courage needed to face those memories. “It’s so easy, in the face of extreme grief, to suppress it”, he observed.

But entering the box for a second time there’s a palpable sense that people, having made that choice to look much deeper into their feelings and emotions, they were more ready to engage with and accept the changes they had undergone, that it was OK to ‘feel happy in your life and find joy’ again. Referencing Donald Byrd in the film, Johnson said: “The way he channelled his trauma into dance was amazing. He took his life’s passion and his skillset, and he used it for good. That experience didn’t just heal him in the moment but became the framework for his entire career since. It’s remarkable”.

Jane compared this with her own experience : “Post-traumatic growth is where your value of life lies. My post traumatic growth has brought me to a place where I value each minute more than I ever did before. I would never have believed that, after Josh died. If someone had said that to me, ‘Oh, don’t worry, eventually you’ll value life’, I’d have said, ‘Please just leave me alone”.

MEMORY BOX – ECHOES OF 9/11 is available on NOW TV – CLICK HERE

When Words are not Enough

In our last posting we promised some more snippets from our forthcoming book When Words are not Enough. This is from Sangeeta Mahajan who, following her son’s death from suicide, took up the Japanese art form Ikebana, a form of flower-arrangement which she found “brought home the fundamental truth of impermanence”.

“Ma is a Japanese word that can be roughly translated as ‘gap’, ‘space’ or ‘pause’. It is best described as a simultaneous awareness of form and non-form, bringing the ‘seen’ into a sharper focus because of the presence of the ‘unseen’ … Saagar’s physical absence has slowly transformed itself into an ethereal, scintillating space that gives prominence to the love and blessings that are present in my life.“

Sangeeta Mahajan

Thanks for reading

Jane and Jimmy (June 2022)